How to Acclimate to High Altitude (and Avoid Altitude Sickness Above 8,000 Feet)

On Elevation Sickness, Acclimatization, and Preparing for the Injustices of 14,000 Feet.

To be frank, the highest point in Florida right now is the laundry pile in my bedroom closet. Living just below sea level doesn’t exactly make me the poster child for altitude expertise. My home state of Michigan is mainly flat, too, so no - I didn't grow up training for the thin-air trials of mountain life.

Despite this, the siren call of rugged peaks and crisp alpine air has kept our travel plans climbing to new heights. These unparalleled experiences also bring new challenges, as thin air makes it harder for our bodies to adapt.

Prior to the Colorado Trail, I had a lot of anxiety about whether or not I was going to be able to tackle elevations as high as the majestic Fourteeners. People often begin to feel the effects of altitude sickness (if at all) by around 8,000 feet. It did not bring me comfort to know that people who live at or below sea level are more likely to suffer from the negative side effects (which are outlined below).

My main concern was that, if I started throwing up or getting a bad headache on the trail, the only option from there would be to start descending.

Why Altitude Hits Sea-Level Hikers Harder

At just 12,000 feet, the oxygen level is roughly 40% lower than at sea level. This means the body is working 1.67 times as hard to oxygenate itself. This has a substantial effect on your sleep, appetite, and overall well-being, impacting everything from your breathing rate to your energy levels and mental clarity. The information provided here will accompany you along your journey and help you achieve those high-mile goals of yours.

Mountains have a way of drawing adventurers from all over the world to high-altitude destinations. If you are hiking, skiing, climbing or just visiting at elevation higher than 8,000 feet, there are a few sage wisdoms to keep in mind. With a bit of preparation, you can minimize risk, maximize your enjoyment, and master any summit.

I found myself reeling for recommendations, obsessively searching up prompts like ‘how to prepare for high altitude symptoms’ and ‘quick fixes for elevation sickness’. I hit up well-traveled friends and rocky mountain experts, pestering them for more high-altitude must haves to add to the list. I even cornered a poor, unsuspecting REI employee to inquire about whether or not there were any magical elixirs for sale there that had passed under my radar during my hunt (yikes, wish I was kidding).

I dove pretty far down the rabbit hole (hey, wrong way!) of altitude, and thankfully I did find the answers I was looking for. After a lot of trial, error, and money wasted, I’m putting my hyperfixation where it belongs: on the Stack.

So, for all of us lowlanders venturing into the clouds… here’s my hard-won guide to prepping for elevation sickness and handling any pesky symptoms that arise.

What Is Altitude Sickness (AMS)?

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), is a condition that can affect anyone who ascends to high altitudes too quickly. It occurs because the air at higher elevations has less oxygen, putting a strain on your body.

Common symptoms include:

Headache

Nausea and vomiting

Dizziness

Fatigue

Shortness of breath

Loss of appetite

Difficulty sleeping

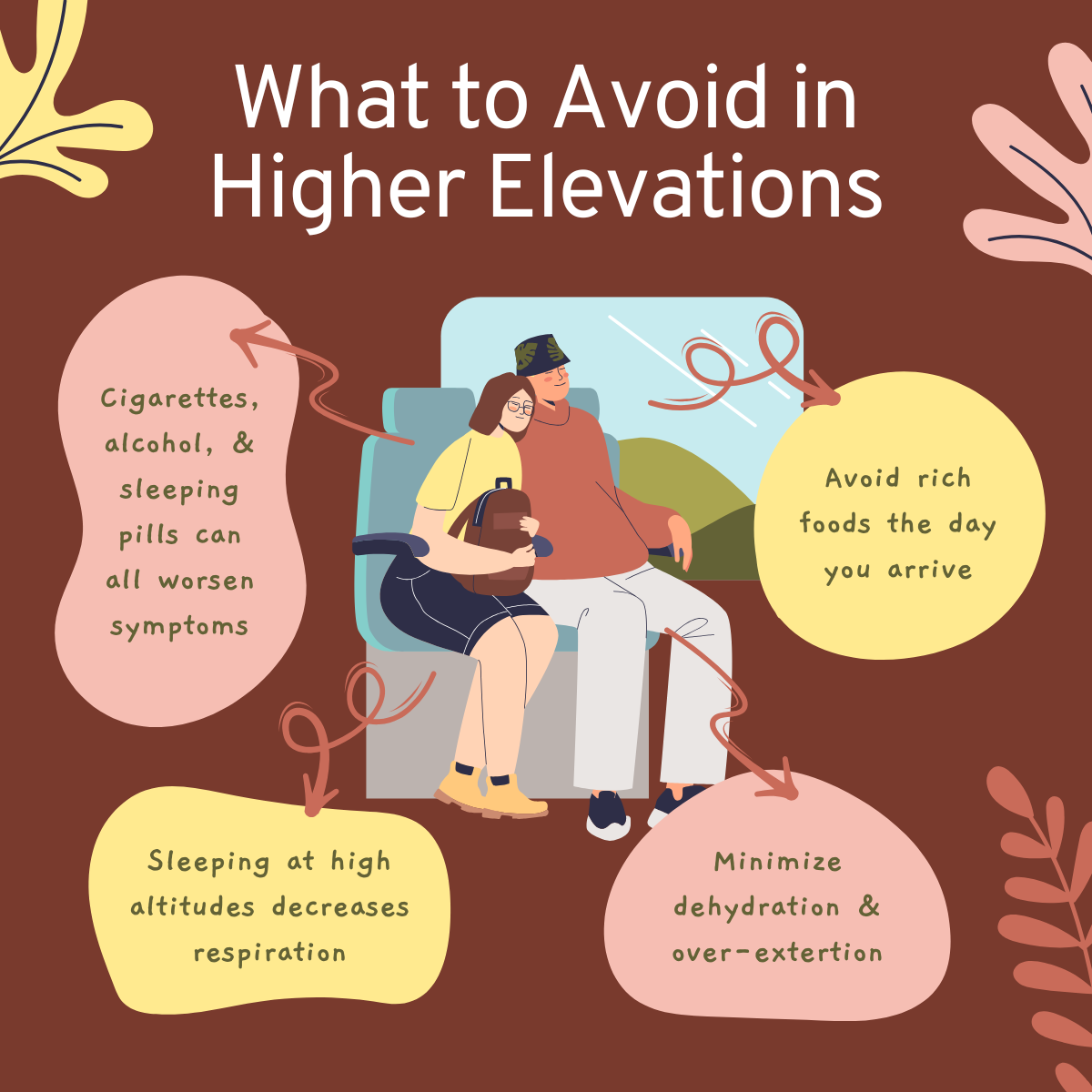

While these symptoms can be mild, they can progress to more serious conditions like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) if ignored. Risk factors include intense cold conditions, heavy exertion, rapid ascent, respiratory depressants and excessive salt ingestion. HACE and HAPE are life-threatening situations with clear alterations in neurological and physiological function, the remediation of which often requires supplemental oxygen (tank) and a hyperbaric bag. Underlying diseases, such as asthma, COPD, pulmonary hypertension, coronary heart disease, sickle cell disease, and pregnancy can put you at even greater risk of developing these life-threatening conditions.

If you find yourself experiencing AMS, take stock of your symptoms and be wary if they start to worsen. Symptoms can happen as early as a couple hours after you arrive at altitude, and last for as long as 1-2 days. If side effects are mild (similar to a hangover) but your vital signs (i.e. pulse, respiration) are regular, you do not need to descend - however, it is not the best idea to continue ascending at this time.

Something that is helpful to recognize at this point is that the only way your condition is going to get better is by limiting your exertion and allowing your body to acclimate to the level of elevation you are at. If you have a prescription medication like Acetazolamide (Diamox), proceed with your physician’s recommendations on proper dosage and administration.

Acclimatization is your body's natural way of adapting to lower oxygen levels. It involves physiological changes like increased breathing rate, red blood cell production, and changes in blood vessel dilation. There is a general rule of acclimating properly, and that’s to let it happen. Do not to skip this step; it’s a critical component of your “elevation foundation”.

While complete ventilatory acclimatization generally culminates in 4-7 days, each day you allow yourself to gradually adapt will bolster your ability to respond well.

How to Acclimate Properly Before Hiking Above 10,000 Feet

Plan Ahead: Take the highest estimated elevation in your current travel plans and base your “staging day” on that, which involves incorporating a rest day (or several) at a mid-altitude point to further aid acclimatization. If you’re tackling one of the Fourteeners like Colorado’s Mount Elbert (14,440 ft), for example, it may make sense to hang out in Buena Vista (7,965 feet) for a couple days before embarking on your hike.

Drink More Water: Hydration is one of the most important (and overlooked) factors when it comes to acclimatization. Keep in mind that, once you are dehydrated, it can take several hours to rehydrate your entire body. Your water intake can either reinforce or hinder your ability to rise above the elevation scaries. Aim for 3-4 liters a day and assume the worst when it comes to options like coffee, alcohol and other dehydrating options.

Mindful Steps to Sleeping: The aim is to climb high and sleep low. Increase your sleeping elevation gradually, ideally no more than 1,000 feet per day above 10,000 feet.

Pace Yourself: Avoid overexertion, especially in the first few days at altitude. Take breaks and check in with body, making sure to listen to your gut. You may even want to pull out the pad and pop a squat if you’re feeling dizzy; getting off those dogs of yours can do a lot for replenishing your energy reserves.

What Changes Above 14,000 Feet

Climbing above 14,000 feet presents unique challenges. The air is significantly thinner, weather conditions can change rapidly, and the terrain becomes more demanding.

There are hundreds of products out there available for purchase that don’t actually help and capitalize off of your fear – like those cans of “oxygen” promising to alleviate altitude sickness. Don't fall for it! Those little cans might make you feel better psychologically, but they simply don't contain enough oxygen to make any real physiological difference. The amount of oxygen you get in a few breaths from a can is negligible compared to what you need to acclimatize.

What Actually Helps (and What’s a Scam):

Macronutrients: Pack high-energy snacks and meals to fuel your body. Complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and protein are essential. Opt for trail mix with a good balance of nuts, seeds, dried fruits, and dark chocolate. Energy bars, jerky, oatmeal, and peanut butter are also great choices. Think high calorie, good-for-you ingredients, and feel free to check out my trail-tested recipes if you’re looking to save money by prepping your own!

Antioxidants: Foods rich in antioxidants (like berries, dark chocolate, and leafy greens) can help protect cells from damage caused by high altitude stress.

Prescription Medications: Diamox (Acetazolamide) is used for the prevention or lessening of symptoms related to mountain sickness in climbers attempting rapid ascent. Like any other prescription medication, however, it comes with drawbacks and a number of unpleasant side effects. Consult your doctor about medications like it to identify if this is the right option for you.

Little Holistic Helpers: While there’s no magic elixir for altitude sickness (trust me, I asked), holistic remedies such as ginger and garlic (easily accessible in capsule or supplement form at your local convenience store) do help alleviate symptoms and support acclimatization. Ginkgo biloba leaf may prove harder to come by in-store, so I would suggest sourcing it online and having it shipped to your door; this herb enhances blood circulation and cognitive function at high altitudes. Like all herbal medicine applications, the FDA wants you to know more research is needed to identify their individual efficacies. They won’t fund it. Ensure there are no interactions or contraindications with these herbs and the medications you are currently using and see if they make a difference for you. Ginger and ginkgo biloba were the two supplements I used in preparation for as well as throughout the Colorado Trail.

Wear Sunscreen: The higher you climb, the closer you get to the sun, and the stronger UV radiation becomes. This means you burn more easily at higher elevations, even on cloudy days. Apply broad-spectrum sunscreen liberally and be mindful of how much you are sweating it off, reapplying as needed. Cover up with UV-protective clothing like long-sleeved shirts, pants, and a wide-brimmed hat. Protect your eyes, and don’t forget to cover your lips, which are vulnerable to sunburn as well!

Physical Fitness: Train beforehand with hikes at lower elevations, gradually increasing the difficulty. A strong base fitness level is crucial for tackling peaks like Mount Rainier (14,411 ft) in Washington. If pre-elevation play is not an option for you because of where you live, be sure to check out my train-to-trail series, where I share all of my expert advice (as a Certified Personal Trainer) on conditioning yourself to even the toughest of trails. Do not make the mistake of assuming that because you are physically fit or follow a standard training regimen, you are equipped to withstand an environment with less oxygen.

Deep Breathing Techniques: Practicing deep, rhythmic breaths can help improve oxygen intake and reduce anxiety. When you control your breathing as you hike, you maximize oxygen uptake, regulate your heart rate, and enhance your recovery. During strenuous hikes, overexertion can play an unsightly factor, and practicing deep breathing helps improve your endurance, even helping to reduce muscle soreness by promoting relaxation and a stronger mind-body connection. Keep in mind here that slowing down your breathing rate is not the intention; you are simply controlling your breathing, which will be labored and require mindfulness to continue ascending.

Spa Day (No, Seriously): Hear me out, because this may have been as close to a magic elixir as I personally got while out in the mountains of Colorado. Soaking in hot springs can offer several benefits for acclimatization. The heat improves your blood circulation and relaxes your muscles, while the minerals in the water help replenish electrolytes lost through sweating. While you’re at it, find a hot spring that also offers a cold river plunge, like the unsuspecting Cottonwood Hot Springs Inn & Spa in Buena Vista, CO. By switching between both the hot springs and cold, rushing waters accessible there to guests, you’ll not only release a bundle of heat shock proteins in your body (which play a crucial role in cellular repair and protection) but also reset your lymphatic system (which removes waste and toxins from the body). Some people may also find acupuncture helpful for managing altitude sickness symptoms, though research is limited.

Pro Tip: Use Staging Days for Acclimatization

If you’re looking to plan ahead with a Staging Day (or two or three), here are some great examples of where you can stay prior to ascending to higher altitudes:

Mount Whitney (14,505 ft), California: To acclimatize for the highest peak in the contiguous U.S., consider spending a few nights at higher elevations before your climb. Options include:

Whitney Portal (8,360 ft): The main trailhead for Mount Whitney provides a good starting point for acclimatization.

Cottonwood Lakes Trailhead (10,000 ft): This trailhead offers access to beautiful lakes and higher elevation camping.

Mount Rainier (14,411 ft), Washington: Prepare for Rainier's challenging glaciers and high elevation by gradually increasing your altitude.

Camp Muir (10,080 ft): A popular base camp for summit attempts, spending a night here can significantly aid acclimatization.

Panorama Point (6,800 ft): A moderate hike with incredible views of Rainier and the surrounding landscape.

Denali (20,310 ft), Alaska: Conquering North America's highest peak requires extensive preparation and acclimatization.

14,200-foot Camp: A common acclimatization camp on the West Buttress route, allowing climbers to adjust to the extreme altitude.

7,800-foot Camp: Another acclimatization point on the mountain, offering stunning views and a chance to test your gear.

Mount Elbert (14,440 ft), Colorado: The highest peak in Colorado offers several options for acclimatization:

Leadville (10,152 ft): This historic mining town provides a great base. Explore the town's rich history, enjoy the scenic views, and take advantage of the many hiking trails in the area.

Buena Vista (7,965 ft): Located at the foot of the Collegiate Peaks, Buena Vista offers a variety of outdoor activities. Hike to the summit of Mount Princeton (14,197 ft) for a challenging day trip.

Keep in mind, these are just a few examples of how you can strategize depending on your intended location, and there are often many other variables at play - such as the time of year, personal preference to nearby activities or landmarks, and the overall fitness level of the group you travel with. Altitude sickness can affect anyone, regardless of athletic ability.

Listen to your body, descend if symptoms worsen, and don't hesitate to seek medical attention if needed. Always research your specific destination and consult with experienced climbers or guides for personalized advice.

By understanding the effects of altitude, acclimatizing properly, and preparing thoroughly, you can safely and enjoyably conquer the magnificent heights that await you.

Go with love!

— Freda Heights

Very helpful!